I think you should buy the Apple Vision Pro! I use it all the time already and it's very nifty!

Zuberi

Related Reading:

Why Texas Is Banning Banks Over Their ESG Policies

Texas started a war against 'anti-fossil fuel' banks. It could cost taxpayers $22 billion.

UBS Banker’s Frustration Exposes Cracks in World of Climate Finance

The world’s biggest banks are quietly hanging on to carbon-intensive clients because of what they see as unrealistic demands from regulators and civil society — and the threat to their fees. By Alastair Marsh and Natasha White March 27, 2024 at 4:00 PM CDT

Judson Berkey didn’t hold back.

It was early February and the UBS Group AG banker had WebEx-dialed into a meeting held on the 17th floor of the Japanese Financial Services Agency’s building in the Kasumigaseki district of central Tokyo. The closed-door gathering with representatives of the Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank and public officials from around the world was billed as a “check-in” for regulators to ask key market participants how they were dealing with the growing tapestry of rules and guidelines around transitioning the economy away from high-carbon assets.

What might otherwise have been a staid conference took an unexpected turn as Berkey, group head of engagement and regulatory strategy at UBS, interjected. The finance industry was being asked to align loans, investments and capital-markets portfolios with a global warming trajectory of 1.5C, while the planet may in fact be hurtling toward a 2.8C increase from pre-industrial times, he noted. The Financial Services Agency headquarters in Tokyo.Photographer: Akio Kon/Bloomberg

The upshot: The world’s biggest banks can’t live up to the green regulatory ideal unless they start dumping huge numbers of clients worldwide at a reckless pace and also roil economies in large swathes of the globe that primarily rely on dirty fuels. Faced with that dilemma, many lenders are quietly reeling in their climate ambitions.

“Banks are living and lending on planet earth, not planet NGFS,” Berkey told the group in an impassioned speech, alluding to the Network for Greening the Financial System, a collection of central bankers that creates model scenarios for how the energy transition may evolve. Details of what transpired at the meeting hosted by the Financial Stability Board — a coordinator of global regulations — came from people who were in the room but asked not to be named discussing private talks. Berkey confirmed his participation, declining to say more.

The UBS banker’s outburst, which got little pushback from those present, exposes the cracks emerging in a multitrillion-dollar transition finance project, and taps into what’s rapidly becoming one of the most contentious issues in the global banking industry. In private, senior bankers in sustainable finance divisions in London, New York, Toronto and Paris grumble about unrealistic expectations from regulators, civil society and climate activists around the industry’s role in getting the planet to net zero.

The standoff that’s brewing is setting the stage for a showdown at the heart of the ESG movement, where environmental, social and governance considerations are being pitted against old-fashioned capitalism.

As the gatekeepers of capital, banks can play a central role as catalysts for cutting greenhouse gas emissions. Private capital will need to cough up the lion’s share of the $5 trillion to $10 trillion in annual commitments needed to pay for the green transition, and according to hedge fund billionaire Bridgewater Associates founder Ray Dalio, that will only happen if there’s “a return on the money.” Adair TurnerPhotographer: Dominika Zarzycka/NurPhoto/Getty Images

Climate change is “an economic externality, and you can’t expect a free market to deal with it voluntarily,” Adair Turner, who ran Britain’s financial regulator during the subprime and euro-zone debt crises and is now chair of the Energy Transitions Commission, said in an interview. Most of the transition away from high-carbon activities toward greener business models “will be financed by private institutions making, broadly speaking, profit-maximizing decisions,” he said.

Banks that had enthusiastically committed to align their entire operations with net zero goals are having second thoughts as the real-world ramifications of acting on those pledges become painfully apparent.

For instance, doing business in the energy sectors of coal-dependent countries like South Africa, Poland and Indonesia would be off limits.

Not only do the commitments make it harder for banks to serve commodities clients like Glencore Plc, but even companies not always associated with heavy carbon footprints are ending up in the crosshairs. Nvidia Corp., the wildly successful tech colossus, has an implied temperature rise of 4C and cosmetics giant L'Oreal SA is at an eye-popping 6C, meaning their business models are currently aligned with a trajectory of devastating global warming, according to data compiled by Morningstar Inc. The Voyager building at Nvidia headquarters in Santa Clara, California.Photographer: Marlena Sloss/Bloomberg

“Our net zero commitments are about being our clients’ lead partner and are consciously taken around the idea that we need to be there with our clients and our clients need to succeed, not that we need to hyper select clients in order to get to net zero somehow faster or better,” Jonathan Hackett, head of sustainable finance at Bank of Montreal, said in an interview.

Some of the world’s biggest lenders, including Deutsche Bank AG, HSBC Holdings Plc and Bank of America Corp., are adding caveats to their restrictions on financing coal, the planet’s most-polluting energy source.

BlackRock Inc. Chief Executive Officer Larry Fink says he has stopped using the term ESG and emphasized the world’s largest asset manager's work with energy firms in a letter to investors this week. The firm has scaled back its participation in international climate investing alliances.

In February, a string of financial heavyweights, including JPMorgan Asset Management, Pacific Investment Management Co. and State Street Global Advisors, withdrew from Climate Action 100+, the world’s largest investor group formed to fight global warming. Lenders, including HSBC, decided to withdraw applications to get their climate goals certified by the United Nations-backed Science Based Targets initiative. Other such voluntary climate alliances have been shaken by similar walkouts of late. Fossil Fuel Financiers

Twenty of the world's biggest banks have allocated a total of over $2 trillion in loans to fossil fuels since the Paris Agreement was struck in 2015.

Source: Bloomberg

Spokespeople for the firms said the moves didn’t reflect a reduced commitment to climate finance. Behind the scenes, people close to the decisions to exit point to the inconvenience of continued membership, spanning everything from the risk of being sued by anti-ESG agitators in the US — especially in the event former President Donald Trump returns to the White House — to the growing mountain of paperwork associated with upholding climate targets. There’s also lost revenue.

“For banks with substantial capital markets businesses, like those competing with the JPMorgans of the world, it’s fee income that’s on the line here,” said James Vaccaro, Chief Catalyst at Climate Safe Lending Network, a group that helps the finance industry figure out how to cut its carbon footprint. “Ditching clients off track from 1.5C means losing major lines of revenue.”

When climate consciousness erupted onto the financial stage in 2021 at the so-called COP26 summit in Glasgow, major western banks clamorously committed to reduce their carbon footprints. Financed emissions — those that arise from lending and investing — would fall in line with a pathway to achieve net zero by 2050, they pledged. In tandem, most of them promised to pour a big chunk of money — anywhere between $750 billion and $2.5 trillion per bank — into green and sustainable deals by the end of this decade.

But all that was before they had rolled up their sleeves and done the math. Declarations of intent on slashing greenhouse gas emissions “over projected” what the industry could do, said Adam Matthews, chief responsible investment officer for the Church of England Pensions Board. There’s now a “gradual peeling away of flaky members as the penny has dropped that this is much harder than a photo call and press release,” he said. Adam MatthewsPhotographer: Betty Laura Zapata/Bloomberg

Inside the finance industry, irritation hit a new level after the publication of an ECB paper in January stating that 90% of the euro-zone banks it analyzed are “misaligned” with the goal of limiting global warming to 1.5C. The central bank called this a “staggering” outcome.

The ECB noted that many banks depend largely on clients in energy-intensive sectors for revenue. It looked at six industries — power, automotive, oil and gas, steel, coal and cement. On average, these exposures amount to 15% of their highest-quality capital, although the ECB cited “significant variation among banks.” In other words, widespread losses on loans to high-carbon sectors would probably wipe out a large chunk of banks’ financial reserves.

Defining what can go under the rubric of the green transition remains a work-in-progress, even as lenders including Barclays Plc, BNP Paribas SA and Citigroup Inc. create new investment and corporate banking teams for it.

In some cases, banks are even placing the financing of coal plants under an ESG banner. Lenders are looking for ways to hold on to clients in an array of high-emitting industries spanning cement to shipping and aviation. HSBC has made clear that many clients within these industries will only reach net zero if nascent carbon-reduction technologies can be sufficiently scaled up. The Countries Most Reliant on Coal

South Africa, China and India rely on coal for over half of their energy needs.

Source: Energy Institute's Statistical Review of World Energy, 2023

Other includes oil, natural gas, nuclear, hydroelectric and other renewable energy sources.

Coal has tended to face the tightest financing restrictions of all fossil fuels, and international packages to help developing countries transition away from coal have struggled to attract western bankers concerned their involvement would breach their climate policies.

Now, some banks are testing the waters.

A January request for proposals from banks to help finance a coal deal linked to one of the so-called Just Energy Transition Partnerships in Indonesia received a “strong response,” a spokesperson for the Asian Development Bank told Bloomberg. HSBC, Standard Chartered Plc and Bank of America are among lenders that have pitched for the deal that would finance the early closure of the Cirebon-1 coal-fired power station in West Java, Bloomberg has reported. The only way the banks can do that is by expanding their exposure to coal in the medium term.

Cirebon is one of hundreds of coal-fired plants that power homes and industry across Asia. Unlike in the US or Europe, many coal plants in Asia are still just a few years into an estimated lifespan of roughly four decades. They’re also locked into long-term power agreements and have investors who expect the returns they were promised when they allocated funds to the plants. So shutting them early comes at a significant financial cost. The fishing village of Waruduwur near a coal-fired power station in Cirebon, Indonesia.Photographer: Muhammad Fadli/Bloomberg

“Getting to net zero in time won't be possible unless we all work together to find ways to finance the credible early retirement of Asia's relatively young coal power assets, even if it looks like our coal-related emissions go up in the short term,” said Celine Herweijer, HSBC's chief sustainability officer. “This is about avoided real world emissions.”

The bank published an updated coal policy in January, which shows it now applies a “risk-based approach” to coal projects that might otherwise have been excluded. Herweijer said there's work under way in the industry to separately account for coal-related emissions if they’re the result of financing credible early-coal retirement initiatives.

But some global banks and investors say continued ties with coal just isn’t worth the risk.

“It’s a bit of a slippery slope,” said Thibaud Clisson, climate lead at BNP Paribas Asset Management. The world needs to “get rid of coal as soon as possible, so at this stage, we don’t want to take this opportunity to be less strict,” he said.

Alice Carr, executive director of public policy at the world’s biggest climate finance coalition, the Glasgow Financial Alliance for Net Zero, or GFANZ, says “financial institutions don’t really want to do these kinds of [early coal retirement] transactions presently because we need the right guardrails and there’s a lot of reputational risk if you don’t get them right.” GFANZ is co-chaired by Mark Carney, who is the chair of Bloomberg Inc.’s board and a former Bank of England governor, and Michael R. Bloomberg, the founder of Bloomberg News parent Bloomberg LP.

For Climate Safe Lending’s Vaccaro, it’s how banks go about it that’s important. The opportunity to pivot to green financing is “big enough” to offset some of the lost revenue of dirty clients, but banks are unlikely to seize it if they continue with their “doublespeak” on both embracing sustainability and maintaining business as usual, he said.

Climate activists are worried. Experience suggests that banks and investors “love nothing better than a good policy loophole,” said Paddy McCully, senior energy transition analyst at French climate nonprofit Reclaim Finance. “If one exists, the chances are high they will pour some money through it.”

Meanwhile, investors sticking with carbon-heavy assets say those staying away risk ignoring the real issues in the wider economy. Fumitaka NakahamaPhotographer: Shoko Takayasu/Bloomberg

Many current policies restricting investment in such companies “create a bias” that hurts emerging markets, according to Diana Guzman, chief sustainability officer at Prudential Plc. “Divestment isn’t going to be the solution,” said Fumitaka Nakahama, group head of global corporate and investment banking at Mitsubishi UFJ Financial Group Inc.

As they balance the needs of their clients against their green commitments, veterans of global finance say they want regulators to be honest and acknowledge that progress on climate is slow, and that without the right incentives, bankers won’t play the role expected of them.

“It was always convenient for finance to be projected as the savior on climate, when in reality, finance can only go so far if the enabling policy environment isn’t there,” according to the Church of England Pensions Board’s Matthews.

That was the point UBS’s Berkey made during the Tokyo meeting, and according to those who were in the room, when he had finished speaking, everyone could see “the wheels turning” in the regulators’ heads.

— With assistance from Nicholas Comfort

Evidence from the criminal trial of Sam Bankman-Fried suggests fraud was built into FTX from the very beginning.

By Zeke Faux and Max Chafkin March 27, 2024 at 4:00 PM CDT

Sometime between FTX’s collapse and Sam Bankman-Fried’s fraud conviction a year later, a consensus formed about the onetime boy genius of cryptocurrency: His wild, curly hair and beanbag chair naps at the office were largely for show, but his company FTX, which had been used by millions of people to buy and sell digital currencies, was the real deal. The crypto faithful see FTX as an almost-success story—if only its owner hadn’t taken customer money to cover side gambles. As the author Michael Lewis put it on 60 Minutes, “They actually had a great, real business.”

That idea has been bolstered by a twist in the FTX bankruptcy: When the company collapsed, $8 billion in customer funds had vanished, but the lawyers running it now say they expect to recover enough money to pay back everyone in full. Bankman-Fried’s allies have used this to suggest that the customer funds weren’t so much stolen as they were redirected into at least a few surprisingly good investments. “Whatever else might be said about Bankman-Fried, he was a brilliant businessman,” the law professors Ian Ayres and John Donohue wrote in a recent essay arguing he was wrong to even declare bankruptcy. His lawyers have used this argument to call for a light sentence; on March 28 a federal judge will decide whether to go easy on him or send him to prison for 40 years or more, as prosecutors are seeking. Sam Bankman-Fried, co-founder and former chief executive officer of cryptocurrency exchange FTX, at his arraignment hearing in Manhattan federal court in New York on Dec. 22, 2022, in this courtroom sketch.Photographer: Jane Rosenberg/Reuters

Meanwhile, the crypto industry is acting as if nothing went wrong. The price of Bitcoin is near a record high; also booming are so-called memecoins, a neologism referring to tokens that don’t even pretend to have a real business behind them beyond vibes. The bulk of trading still occurs on exchanges located in countries with extra-light regulation. Crypto boosters have even spun Bankman-Fried’s conviction—along with a guilty plea from the former head of the world’s largest exchange, Binance’s Changpeng Zhao, to criminal charges including laundering money for terrorists—as a positive. “We now have an opportunity to start a new chapter,” Brian Armstrong, the chief executive officer of Coinbase Global Inc., wrote on the social network X. In other words: Don’t worry, it’s safe to buy crypto again.

But Bankman-Fried’s case revealed a version of the former billionaire that’s more disturbing—and especially troubling for an industry bent on sweeping the whole episode under the beanbag. According to an examination of trial testimony, thousands of pages of exhibits and interviews with insiders, Bankman-Fried’s rise appeared to rely on tricking customers, investors and banks almost from the very beginning. His genius, if one can call it that, was recognizing that the mania around crypto would enable him to get away with totally disregarding the rules. Bankman-Fried sits near a screen showing him shaking hands with Binance CEO Changpeng Zhao in this courtroom sketch from Oct. 10, 2023.Photographer: Jane Rosenberg/Reuters

Imagine crypto trading as a video game. Bankman-Fried certainly did. His gaming addiction was a running theme throughout Lewis’ bestselling book Going Infinite: The Rise and Fall of a New Tycoon and was well known even to his own investors, who caught him playing League of Legends during a pitch meeting. Helping himself to FTX customer money was like turning on invincible mode. It let him gamble like he’d never lose and spend like he’d never go broke. His race to billionaire status was so fast that one tech blogger compared it to a speedrun of The Legend of Zelda.

Bankman-Fried’s trading wasn’t as profitable before he found his cheat code. Back in 2017, when he started a hedge fund called Alameda Research, he relied on personal connections for funding and even then had to agree to pay punishing interest rates. Bankman-Fried, then 25, had worked at the Wall Street firm Jane Street Capital, but his capital came mostly from people he knew from the effective altruism movement, whose adherents believe getting rich quickly and giving money thoughtfully could help solve the world’s ills.

Alameda’s first big investor was an early Skype engineer named Jaan Tallinn, who charged the hedge fund an annual interest rate of 43%. He and a handful of other wealthy effective altruists lent Alameda more than $100 million. But within a few months, Bankman-Fried had suffered a series of big losses, and many of his investors demanded to be paid back. He somehow still cultivated an image of perpetual success and immense wealth, often with a philanthropic bent. This image had the effect of obscuring an essential truth about his empire: For a business that purported to be wildly profitable, it was weirdly low on cash.

“This was something he talked about a lot,” Caroline Ellison, the former CEO of Alameda, said in her court testimony. “He said that we should be trying really hard to find new sources of money.” Ellison pleaded guilty for the role she played in defrauding customers. Caroline Ellison weeps as she testifies during Bankman-Fried’s trial on Oct. 11, 2023.Photographer: Elizabeth Williams/AP Photo

Until Ellison took the stand, Bankman-Fried’s official story about the founding of FTX had basically stood unchallenged: He started the company in 2019, he often said, because Alameda had been doing a lot of crypto trading, and he thought he could build a better exchange. He pitched FTX to customers as a safe place to buy, sell and store their digital currencies. Ellison offered an alternative explanation: “He said that FTX would be a good source of capital,” she said in court. The implication was that Bankman-Fried started FTX as a means to fund high-risk investments for Alameda. This, to be clear, is the opposite of what he told customers.

Testimony from Bankman-Fried’s former employees, as well as code from FTX’s website introduced as evidence in the trial, showed his pitch to be hollow. For example, the total balance for an “insurance fund” listed on FTX’s website to reassure customers was actually made up using a random number generator. And just months after the exchange opened, FTX created a backdoor for Alameda, a mechanism within FTX’s code known internally as “allow negative.” It overrode FTX’s internal controls, making it possible for Alameda to borrow almost unlimited sums from FTX customers. It also helped that, to deposit money at FTX, customers had to send it to Alameda. They were led to believe the funds would be passed along and held on their behalf. Instead, Alameda in many cases just spent the money.

Bankman-Fried acknowledged most of this at the trial but said none of it was malicious. His former employees on the witness stand, however, suggested he knew the company was short on cash and tried to hide it. FTX co-founder Gary Wang testified that, in late 2019, he overheard his boss telling an Alameda trader it was OK that the fund was borrowing money from FTX customers because the exchange had earned more than enough in trading fees to cover the investments. A few months later, Wang said, he discovered Alameda had already blown through that already questionable guideline. Gary Wang testifies during Bankman-Fried’s trial on Oct. 6, 2023.Photographer: Elizabeth Williams/AP Photo

The truth was obvious to him: “Alameda was taking customers’ money,” Wang testified.

All the evidence makes clear that FTX wasn’t a good company run by a bad guy. It was a business that was crooked almost from Day 1. That’s a problem for the entire crypto market. Its supporters pitch the products as an alternative to a mainstream financial system they say is rigged against ordinary people. But the conditions that let Bankman-Fried rig markets at FTX remain unchanged. If anything, they may get worse: In a contentious political environment, crypto boosters are spending lavishly to influence lawmakers and try to soften regulations while marketing digital tokens as a sensible choice for novice investors. Which is pretty much what Bankman-Fried did to maximize his fraud.

It wasn’t hard for Bankman-Fried, armed with the cheat code of unlimited customer cash, to make FTX look more successful than it actually was. The company famously spent hundreds of millions of dollars on luxury real estate in the Bahamas and made eye-popping investments in crypto companies—including $50 million for a startup that sells digital copies of cartoon monkeys, $45 million for the investment firm run by former Trump White House spokesman Anthony Scaramucci and $400 million for an attempted bailout of a failing crypto lender. Bankman-Fried also spent lavishly on donations to politicians and celebrity endorsements. An Instagram post showing Bankman-Fried with singer Katy Perry.Source: SDNY US Attorney’s Office

More important, perhaps, the cheat code allowed FTX to paper over losses that would’ve sunk a normal business. According to Wang, FTX lost about $1 billion in a 2021 incident when a trader exploited a bug in its software using a thinly traded token called MobileCoin. The loss would’ve wiped out all the revenue the exchange had generated since it started, according to internal figures filed as evidence in court, and might’ve sent a version of FTX that wasn’t cheating straight into bankruptcy. Instead, Bankman-Fried instructed employees to count the loss as Alameda’s.

At the trial, Wang recalled Bankman-Fried’s explanation: “He said that FTX’s balance sheets are more public than Alameda’s.” In an interview with Bloomberg Opinion columnist Matt Levine several months after the MobileCoin incident, Bankman-Fried bragged that the company’s risk management was so good that “we’ve never had a day, I think, that there was more money that we lost in blowouts to revenue than trading fees.” This was a lie. A court image shows Bankman-Fried at his desk at FTX.Source: SDNY US Attorney’s Office

Around the same time, Bankman-Fried was negotiating with venture capitalists to raise money for FTX. He sent them reports that omitted the giant loss. “Congrats on the amazing exchange performance,” Zack Rosen of Ribbit Capital wrote in response to Bankman-Fried’s pitch. In July 2021, FTX raised $900 million. A former employee involved with the investment, who asked not to be identified because of the company’s ongoing litigation, says the deal would never have closed if Bankman-Fried hadn’t covered up the loss.

Even with the influx of venture capital, Alameda borrowed more and more from FTX. One of the big costs was buying out an investment that Binance had made in FTX so Bankman-Fried could disentangle his company from a rival. “We don’t really have the money for this,” Ellison testified that she told Bankman-Fried.

“That’s OK,” Bankman-Fried replied, according to Ellison. “We have to get it done.” Ellison testified that they used an additional $1 billion of FTX customer deposits to close the deal with Binance. Ellison points out Bankman-Fried during his fraud trial on Oct. 10, 2023.Photographer: Jane Rosenberg/Reuters

Later that year, as crypto markets boomed, Alameda borrowed even more to make big bets on newly minted digital currencies known within the industry as “shitcoins.” As Ellison once put it in a post on Twitter, “figure out when the market is going to go up and get balls long before that.” Alameda was also investing in so-called yield farming, which in practice often amounted to lending money to Ponzi schemes and hoping to get out before they collapsed. There also was a $150 million expense Ellison listed as “the thing” on a report she prepared. The thing, prosecutors alleged, was “one of the largest foreign bribes ever paid by a US person,” in this case to Chinese government officials.

In mid-2021, before Bankman-Fried’s spending spree really got going, Ellison warned him that Alameda’s debts were looking risky. Bankman-Fried asked her to invest an additional $3 billion in venture capital, even though Alameda had already helped itself to at least $2 billion from FTX customers and borrowed $9 billion from other lending firms. The hedge fund’s biggest asset was a giant pile of cryptocurrencies that Bankman-Fried had either created himself or was closely associated with. Ellison calculated that without these so-called Sam coins, FTX owed almost $3 billion more than it had. She testified telling Bankman-Fried that if they made the investments, and the market crashed and lending firms asked for their money back, Alameda would go broke and FTX would fail.

What happened next is, well, they made the investments, the market crashed, Alameda went broke and FTX failed. Before long, Bahamian police were knocking on the door of Bankman-Fried’s $30 million penthouse.

After FTX filed for bankruptcy, Bankman-Fried didn’t know what to do. He wrote a list of potential strategies, including: “File the doc with problems about the Chapter 11 process” (Option 1); “go on Tucker Carlsen [sic]” and “come out against the woke agenda” (Option 3); “Have Michael Lewis interview me” (Option 11); “radical honesty” (Option 15). Ultimately he settled on a version of Option 1, blaming the bankruptcy attorneys, and Option 11, finding a sympathetic journalist. He didn’t try Option 15.

Bankman-Fried first said he lost the money through a series of sloppy mistakes. He claimed he wasn’t heeding warning signs because it felt like he had “infinity dollars.” “I f---ed up,” he wrote on Twitter and in testimony he planned to deliver to Congress. Then, in interviews and social media posts, he complained he’d been victimized by “strong-arming” lawyers who’d manipulated him into filing for bankruptcy, which he called “maybe my single biggest f---up.” In a series of unpublished essays titled “Inception,” after the Christopher Nolan movie, he even argued that Sullivan & Cromwell, the law firm in charge of the FTX bankruptcy, had manufactured the narrative that he stole customer funds. (He gave the essays to a crypto influencer, Tiffany Fong, who passed them on to the New York Times.) “They’ve played it incredibly well,” Bankman-Fried wrote of the law firm, which has defended its conduct as proper. “Were it not destructive to just about everything I care about in life, I would tip my cap to them.”

This argument found a willing audience among some FTX victims eager to blame anyone for what happened, helped spur a class-action lawsuit and was presented in Lewis’ book as a plausible explanation for what went wrong at FTX. Sullivan & Cromwell will get paid hundreds of millions of dollars for its work on the bankruptcy, a figure that critics have suggested is excessive. On the other hand, those fees are starting to look like money well spent, since FTX’s bankruptcy attorneys said in January that they expect to recoup enough money to pay customers back in full.

Bankman-Fried’s attorneys seized on this announcement to offer an audacious counterfactual narrative they hoped would get him a more lenient sentence. “The truth is, there were never losses,” Marc Mukasey, the lawyer representing Bankman-Fried at his sentencing, wrote in a March 19 letter to the judge. “The money has always been available. Assets remain. Each victim quoted in the government’s opposition will receive 100 cents on the dollar—plus interest. This would be impossible if the estate’s assets had disappeared into Sam’s personal pockets.” Bankman-Fried sits with his lawyers Torrey Young and Marc Mukasey on Feb. 21, 2024, as he appears in court for the first time since his November fraud conviction.Photographer: Jane Rosenberg/Reuters

The claims weren’t quite as novel as they might’ve seemed. Fraudsters often insist, as Bankman-Fried has, that they would’ve made all the money back if only they’d been allowed to keep going. And bankruptcy lawyers are often successful in eventually cleaning up the messes they find, even in cases of massive fraud. For instance, the administrators overseeing the Bernie Madoff bankruptcy have returned about 90% of clients’ initial investments.

In the case of FTX, recovering assets rests largely on long-shot bets Bankman-Fried made using customer money that wasn’t his to gamble with, such as a $500 million investment in the artificial intelligence startup Anthropic PBC that’s likely now worth more than $1 billion. The biggest factor is crypto prices. FTX’s debts to its customers were fixed in dollar terms on the day the company filed for bankruptcy, when prices were at a low point.

The estate quickly found about $1 billion worth of Solana tokens and $600 million of Bitcoin and related products, as well as hundreds of millions of dollars of other coins. It hired a manager for the assets: Galaxy Digital, run by Mike Novogratz, a Wall Streeter-turned-crypto enthusiast so committed to the cause that he once got the logo for a token tattooed on his shoulder. (That particular token was later found to be a Ponzi scheme.) Predictably, Novogratz’s firm didn’t try to unload FTX’s crypto right away.

Lucky for everyone involved, prices started going back up. The excitement was driven in part by anticipation that US regulators would approve Bitcoin exchange-traded funds, opening that cryptocurrency to a novel group of potential buyers. Bitcoin started rising, along with the prices of other widely traded tokens including Dogecoin, the original memecoin, which has roughly doubled in value since early 2023. New joke coins that trade on the Solana blockchain emerged, seemingly competing to be as stupid or offensive as possible: dogwifhat (the Dogecoin dog but with a hat), Pepe (the symbol beloved by White nationalists) and for those who found that last one too subtle, a token named simply NAZI. Some of them soared to market caps exceeding $1 billion. The price of Solana itself has climbed more than tenfold since FTX’s failure.

The runup means that, on paper, zombie FTX may have gained as much as $10 billion on its Solana bet, though many of the holdings are locked up and can’t be sold for a few years. FTX’s stash of Bitcoin and other tokens likely gained an additional $3 billion at least, based on filings in the bankruptcy case. If the estate is able to sell them all while the market is hot, it’ll have a reasonable claim to the title of greatest crypto trader in history.

The bankruptcy administrator, John Ray III, tried to downplay this achievement in a letter to the judge in Bankman-Fried’s criminal case. “Even taking into account the potential for achieving anticipated recovery levels, which is by no means assured,” he wrote, “customers still will never be in the same position they would have been had they not crossed paths with Mr. Bankman-Fried.” Bankman-Fried leaves a New York federal courtroom in handcuffs on Aug. 11, 2023. A judge revoked his bail after concluding the former CEO had tried to influence witnesses.Photographer: Elizabeth Williams/AP Photo

Unfortunately, the conditions that allowed people to fall for schemes such as Bankman-Fried’s remain: a massive, speculative and largely unregulated industry rife with fraud and manipulation—and a credulous public eager to bet real money in search of a big score.

Bankman-Fried is still doing what he can to spread the hype. Recently, one of the guards at the Brooklyn prison where he’s being held asked him for crypto trading advice, according to a person with knowledge of the interaction, who requested anonymity citing legal concerns. Bankman-Fried suggested the guard sell his XRP tokens and buy Solana.

I now see what Jersan was saying LOL.

How long have they been pinning this to the top of each post?

Why does MP spike every time the LEAPS come into play?

If we take anything past $127.50 at face value (you can't buy those), the max pain goes all the way up to $180.

What happens when these strike prices go away ("forever") after this week?

I assume they're used as locates in some regard, but what does Citadel lose here?

Most of these odd strikes seem to have been first purchased between 11/7/21 and 11/14/21, any significance I'm missing?

A full year later, we have "yet" to break 76M again.

In this post here https://lemmy.whynotdrs.org/post/381421, we discussed how the numbers are likely much higher than are currently reported. This heavily implicates Cede/DTCC because every quarter requires fraudulent reporting (well played SEC).

But how much higher? We've been at 75M for exactly 4 quarters now. Estimates at the previous pace would have us over 130M shares DRSd at this point.

This would mean there are very few shares actually left out there. Roughly only 26M left to DRS before they truly start to panic from the math-breaking number. The DTCC definitely fucked up by thinking we couldn't buy the entire thing lol.

They warned you there would be FUD, this is it. Keep DRSing and eventually ComputerShare will stop selling to us like they said they would if there are no locates ;).

With that in mind, also don't forget the $149T bullet swap that hits instantly on December 15th. Since they opened that particular short, the stock has seen a 390% increase along with a 430% rise in interest rates, do think they roll that shit over ;)?

I will leave with the same question: Why do you think Gamestop changed the wording from 03/22/2023 onward?

cross-posted from: https://lemmy.whynotdrs.org/post/399058

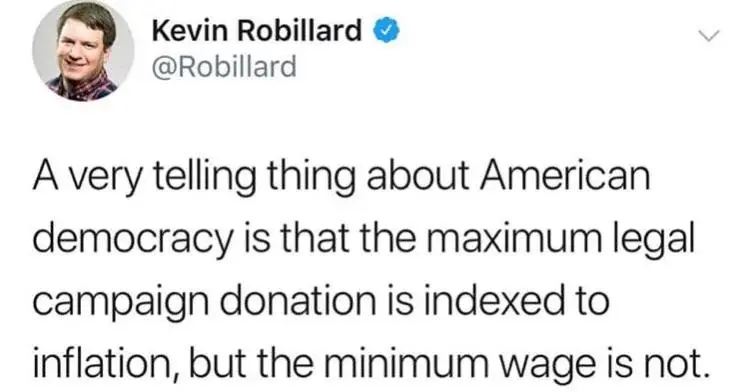

- Donate the maximum amount legally allowed (as an individual).

- Tell the Member that you would like to become a bundler.

(A bundler is a person or small group of people who pool or aggregate contributions "from the community" and then deliver them in one lump sum to a political campaign).

- Once you have raised a sizeable amount, deliver the money to the Senator so they can use it wisely. In turn, ~~trade stock options based on insider information to the tune of millions~~, be super glad that you helped the democratic process!

1% vs the 99%

>how do you transfer back to a broker

Lol

> sell a few

Excuse me? We don't do that here.

> but when you need to sell some shares for funds

If you don't want true ownership, then that's your own fault when you get nothing at the end ;). You can sell directly out of CS without issue (as they have their own broker that they use), but TBCH, I'm fairly certain you already knew that.